-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessica Ogden, Ken Morrison, Karen Hardee, Social capital to strengthen health policy and health systems, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 29, Issue 8, December 2014, Pages 1075–1085, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czt087

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article recounts the development of a model for social capital building developed over the course of interventions focused on HIV-related stigma and discrimination, safe motherhood and reproductive health. Through further engagement with relevant literature, it explores the nature of social capital and suggests why undertaking such a process can enhance health policy and programmes, advocacy and governance for improved health systems strengthening (HSS) outcomes. The social capital process proposed facilitates the systematic and effective inclusion of community voices in the health policy process—strengthening programme effectiveness as well as health system accountability and governance. Because social capital building facilitates communication and the uptake of new ideas, norms and standards within and between professional communities of practice, it can provide an important mechanism for integration both within and between sectors—a process long considered a ‘wicked problem’ for health policy-makers. The article argues that the systematic application of social capital building, from bonding through bridging into linking social capital, can greatly enhance the ability of governments and their partners to achieve their HSS goals.

Field experience related to combating HIV-related stigma and discrimination, backed by current understanding of social capital, led to the development of a simple, three-step model for building social capital.

This model can be applied to help strengthen health policy and programme through advocacy, participatory policy analysis and governance for improved HSS outcomes.

Social capital building achieves these outcomes by creating bonds within communities, connecting communities to each other and linking communities to health and other social system decision-makers.

These connections also occur within health system communities of practice to improve communication and open the way for the introduction of new ideas, norms and practices.

Social capital building across social development sectors can support the integration of these sectors to improve social development overall.

Introduction

There is increased interest at national and international levels to make strategic investments in health policy and health systems strengthening (HSS) (Frenk 2010), and to explore the potential of social capital—or the power of networking based on a strengthened sense of belonging, trust and reciprocity—to leverage the resources needed to improve the health of citizens. This interest emerges out of concern that despite significant progress in addressing key global health and social issues (United Nations 2011; see also Wilmoth et al. 2010), and in the face of an abundance of affordable and effective life-saving technologies, medicines and knowledge, inequities in health outcomes continue to expand, both within and between countries and subpopulations (Marmot et al. 2012; Africa Progress Panel 2012). This is largely due to poorly organized, siloed and often under-resourced health systems that focus on individual medical outcomes and curative care, with insufficient attention to prevention and the broader social determinants of health and illness (Blas et al. 2011; CSDH 2008). Opportunities to work across health and social development sectors and to build intersectoral collaboration and programming are often not maximized (e.g. Kickbush and Buckett 2010; Baum and Laris 2010), exacerbating the challenges inherent in vertical programming and the isolation of health issues in the context of larger development challenges.

Compounding the problem are the challenges faced by system structures to involve affected communities—those whom health and development services are meant to serve—in policy-making and service delivery processes. The need to include the priorities, knowledge and experience of those receiving health services in the design and implementation of policies and programmes is reflected in the principle of greater involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS (GIPA) which emanated from the 1994 Paris AIDS Summit and the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) (UNAIDS 2007; United Nations 1994).

This article recounts experience engaging community voices to improve the effectiveness of health programmes and offers a systematic process for applying social capital approaches to strengthen health policy and health service delivery. The aim is to stimulate debate about the usefulness of social capital for HSS and health policy, and to propose a simple, but systematic, three-step process that can support governments and development agencies in their efforts to appropriately engage communities and community networks; develop systems within health services to collaboratively monitor and improve health policy and the provision of care; and provide a framework for improved measurement of social capital processes and impacts.

Methodology

Since a number of excellent reviews already exist (e.g. Kawachi et al. 2010; Wakefield and Poland 2005) this article does not attempt a systematic review of the literature on social capital and health.

Rather, we draw on relevant literature and extensive field experience to propose a simple process for applying social capital to HSS and health policy. Its aim is to stimulate debate and guide policy-makers in efforts to engage communities, build focused networks and move experience into action that strengthens policy and health systems.

The experience on which the proposed process—or model—is based was gleaned primarily from working with community-based groups and networks in catalyzing action against HIV-related stigma and discrimination (e.g. USAID/Health Policy Initiative 2010; Hull et al. 2010; Kay and Datta 2010; Xia and Stephens 2011; Morrison et al. unpublished data). This work underscored the usefulness of social capital concepts and processes for enabling community-based groups to shift from a sole focus on internal support to co-operative action, and participatory policy analysis and implementation. The model also derived from the experience of those working in family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) and maternal health, such as the White Ribbon Alliance’s (WRA) work on safe motherhood. Missing in the current landscape was a replicable model for supporting a more systematic incorporation of these processes into health policy and HSS.

Based upon this experience, we reviewed relevant literature pertaining to social capital theory (1986–2012), social capital in public health practice, health programmes incorporating a social capital approach and social capital as it relates to health policy and HSS. The proposed model builds upon this literature and experience. Web-based search engines consulted included Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, Medline, POPLINE, Ovid Gateway and JSTOR. Additional references and materials were sourced through the reference lists of the documents identified. Both peer-reviewed journals and the grey literature were consulted, since many new and emerging ideas and projects have not yet been described in the scholarly press.

Theory: understanding social capital in the context of public health

The term social capital has been used over the past century in reference to social cohesion and investment of individuals in communities (Hanifan 1920), the health of cities (Jacobs 1961) and the effects of civil engagement (Putnam 2000). The term refers to the (usually non-monetary) resources generated through social networking and involvement in community affairs (e.g. sense of belonging, trust and influence). Social capital can be accrued by groups of like-minded people within a community and is strengthened as those groups connect with other networks in pursuit of common goals. Social capital becomes stronger still when these networks expand across levels of power and influence. Social capital as a concept is increasingly being used to help policy-makers and programmers understand how formal and informal networks within and among communities can foster better governance and accountability, as well as contribute to improvements in health, health financing and the equitable delivery of health services.

Despite prevailing interest in the concept of social capital in the context of public health, it continues to be a highly contested idea (Kawachi et al. 2010; Eriksson et al. 2010). There are two competing schools of thought. The social cohesion school (e.g. Portes 1998; Putnam 2000; Szreter and Woolcock 2003; Kawachi and Berkman 2000) understands social capital as being those resources (such as trust, norms, reciprocity) that are available to members of social groups; all members stand to benefit by virtue of belonging, even if they do not participate directly. The social network school, on the other hand, understands these resources (here including also social support, information channels and status) as being ‘embedded’ within an individual’s social network; individuals access these resources only by virtue of their involvement in the network or group (e.g. Lin 1999; Eriksson 2011; Granovetter 1973, 1983; Coleman 1988; Burt 2000).

Kawachi et al. (2010, p. 4) find a practical middle ground between these two perspectives, stating that ‘Both the social cohesion and the network definitions of social capital have merit in pointing out the existence of valued resources [capital] that inhere within, and are by-products of, social relationships.’ This article similarly understands that social capital consists of those resources generated through social relationships that build group solidarity, create networks for action and have the potential to influence policy and create social change. These resources, which include a sense of belonging, trust in social institutions, reciprocity, social influence, access to new information and the ability to impose social sanctions, have the potential to support whole communities, but participation can strongly influence the diffusion and uptake of new behaviours and sustain these changes.

Critics of social capital (e.g. Foley and Edwards 1999; Bourdieu 1986; Wakefield and Poland 2005) have suggested that tightly bounded social networks are by definition exclusionary and run the risk of consolidating power in the hands of a few (those with greater access to resources), further increasing the distance between those speaking and those being spoken for. For application to public health, it is thus essential to understand the overall social, political and economic context in which these networks, and the resources that are produced through them, are situated (Wakefield and Poland 2005; Szreter and Woolcock 2003). The state, political ideology and societal ethics all play a role in creating the conditions for productive social networks to emerge and their impact—for good or ill—on population health.

Some political contexts are more amenable to the development of social capital than others. For example, it has been theorized that more egalitarian societies are more likely to create such an environment because power and control over the resources for health are more evenly distributed, allowing space for networks to develop and flourish (Szreter and Woolcock 2003; Baum 2007; Woolcock and Narayan 1999; Kawachi and Kennedy 2002). Wherever it takes place, Wakefield and Poland (2005, p. 2829) conclude that it is necessary for the application of social capital approaches to ‘explicitly endorse(s) the importance of transformative social engagement, while at the same time recognizing the potential negative consequences of social capital development’.

Practice: forms of social capital

Much of the literature on social capital in the context of public health refers to three types of social capital—bonding, bridging and linking. The approach proposed here suggests that while each ‘type’ can exist in isolation, bonding, bridging and linking social capital (referred to in this article also as group networking, action networking and policy networking, respectively) can be systematically brought together in a process to help strengthen social systems, including health systems, and to foster social change, including health and other social policy.

Bonding social capital

Bonding social capital (or ‘group networking’) refers to the creation or strengthening of trusting co-operative relations between individuals in a group who are similar in the way they define themselves and group membership; they share a common identity around which the network forms to build social cohesion and increase the influence of participants in the broader community. Bonding can take the form, for example, of groups of family planning users coming together to share information and support each other in the consistent and correct use of contraception (e.g. Family Future Project, O’Donnell et al. 2009), or when individuals living with HIV come together in support networks to gain self-confidence, battle internal and external stigma and generate energy for advocacy (e.g. USAID/Health Policy Initiative 2008).

In South Africa, the IMAGE Study brought women in one community together in a two-tiered intervention that sought to improve their ability to understand and prevent HIV and intimate partner violence, while inviting participants to join a microfinance initiative to increase their economic independence and community engagement (Pronyk et al. 2006). The first tier, called Sisters for Life, created a strong sense of group cohesion, trust and civic engagement among the participants increasing their sense of personal empowerment and enabling them to renegotiate their personal identities, question previously taken for granted gender norms condoning intimate partner violence and to effect broader changes in these norms in their community (Kim et al. 2007). Although the intervention did not have a significant impact on HIV prevalence, it succeeded in halving the risk of experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence and improving individual and community empowerment along a number of key indicators (Pronyk et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2007). Qualitative data from the study suggests that these reductions in violence resulted from ‘a range of responses that enabled women to challenge the acceptability of such violence, expect and receive better treatment from partners, leave violent relationships, give material and moral support to those experiencing abuse, mobilize new and existing community groups, and raise public awareness about the need to address both gender-based violence and HIV infection’ (Kim et al. 2007, p. 1798; see also Pronyk et al. 2008). In addition to exemplifying the power of bonding social capital to shift norms and effect change, this work showed that bonding (and bridging) social capital, with its positive impacts on health and wellbeing, can be successfully catalyzed and generated intentionally through programming originating outside a community (Pronyk et al. 2006).

These examples of bonding social capitals show that when groups comes together in a safe space to meet and share new information and ideas it can provide social support for members, while also creating a platform for broader community advocacy and action to promote human rights and stigma mitigation at the community level (Kay and Datta 2010; Morrison 2010; Morrison et al. unpublished data). Such groups may also facilitate the renegotiation of social norms and values that put members at greater risk (Campbell and MacPhail 2002; Gregson et al. 2011; Campbell 2001; Rottach et al. 2009).

Bridging social capital

Bridging social capital (or ‘action networking’) connects different groups or networks to attain a shared objective or set of objectives. While bonding creates cohesion in the group, bridging is about the ways in which disparate groups join up to create change (Evans 1996). The strong bonds between individuals developed through bonding social capital are marked by shared norms and understandings of the world—implying strong relationship ties and a bounded domain of knowledge and knowledge sources. Because it connects otherwise disparate groups, bridging social capital allows for the development of ‘weak ties’, which offer the opportunity for connection outside this domain to other parts of the social system, with different norms, understandings, knowledge and knowledge sources (Granovetter 1973, 1983). An example of bridging social capital would be connecting a professional group of physicians focused on one type of medical condition or issue (such as FP/RH) with a group of physicians focused on a different, but related, condition or issue (such as HIV) to create improved services and outcomes for both areas.

The Tostan Community Development Project is another example of bridging social capital. This project brings community groups together with medical groups and community leaders to stop harmful practices, such as female genital cutting (http://www.tostan.org). Action networking of this kind can add strength to advocacy in support of FP/RH, maternal health and HIV policies, both at the national and global levels. Individual groups may not have much voice on their own, but in coalition with other groups within and across countries, bridged groups can have a powerful say in shaping health policy. The Cairo Programme of Action from the 1994 ICPD offers a powerful example of action networking (bridging social capital)—globally, nationally and locally (POLICY Project 2000).

Linking social capital

Linking social capital (or ‘policy networking’) gives communities access to networks or groups with relatively more power in decision-making arenas—and conversely, can give decision-makers more understanding and influence at the community level. Linking social capital can build on the social cohesion created through bonding and the social action taken through bridged networks in order to bring about policy and/or social change. These are more vertical connections—linking groups with greater access to power or status (and, therefore, resources, such as funding and legitimacy) to groups with less power or status. These types of linkages are vital for enabling ‘bonded’ and/or ‘bridged’ social networks to gain visibility, legitimacy and voice at higher levels of decision-making (Baum 2007), creating conduits for feedback from the community to those with the power to effect change, thus serving as mechanisms for accountability and improved governance.

Policy networking of this kind is particularly important for poor or socially marginalized communities, whose health and well-being are more contingent on the nature of their ties (whether trustful and respectful or oppositional and violent) to formal institutions such as security forces, the justice system, banks and the formal health-care sector (Szreter and Woolcock 2003), as well as to decision-makers (such as local politicians, health policy-makers or health practitioners) whose actions or behaviours directly affect their well-being. For example, linking community-level networks with regional and national health authorities and contraceptive security committees can more effectively improve access to FP services than can community groups acting on their own (Gribble 2010). In this way, linking may be productively thought of as a ‘systems’ model of collaboration, because it relies on the existence or creation of systematic mechanisms for partnership across power structures.

The Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) in South Africa is an example of linking social capital in action. Starting with a small group of committed activists working within the National Association of People with AIDS and bonded through the injustice of a global public health system that denied the poor of their right to antiretroviral medications for HIV, TAC grew into a global human rights organization, championing the rights of all to live healthy, dignified lives.

During one well-known campaign, TAC sought to reduce the price of anti-retroviral medications being provided through the public health system in South Africa—effectively making available to all South Africans what was already widely available to the rich and to those in rich countries. They built their movement from the ground up, rapidly expanding out from a small group of concerned activists by staging protests, fasts and sit-ins and garnering signatures to raise awareness and pressure officials into taking action. From these public events, the campaign moved first into communities, creating a network of committed volunteers. As the campaign gained momentum, TAC began to look outside the country actively forging policy networks—what they refer to as ‘solidarity partnerships’—with activists in Brazil, India, Thailand, the USA and the UK to create a global movement to fight the high cost of AIDS drugs then charged by drug companies. This coalition grew, building new relationships with influential organizations such as Oxfam International, Medecins San Frontiers and the World Health Organization. Eventually TAC and its partners effectively challenged the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement—the policy that protected the rights of pharmaceutical companies to own drug patents and keep prices high—and its application in countries with significant HIV, tuberculosis or malaria epidemics. With the power of the global network behind them, TAC went to court to challenge the patents of multinational pharmaceutical giants for the exorbitant price of essential HIV drugs. These actions—and others, including mobilizing communities and gathering affidavits—led to a more competitive market for AIDS drugs in South Africa. The price of HIV triple therapy fell from about R4500 per month to just below R200. Once prices had fallen to this level, TAC activists were able to push the government to dramatically expand access to HIV treatment to all (Dubula and Heywood 2011; TAC 2010; Mbali 2013).

Thus, using the power of their global policy networks (linking social capital), effectively deploying the language and instruments of human rights, TAC moved from a small group of committed individuals, to a powerful international network, saving countless lives by making AIDS drugs more widely available.

Because it acts on the social and political environment to make the uptake of health-enhancing behaviours more feasible, the processes of bridging and linking social capital among global health governance bodies and within and between health-care professionals can facilitate the uptake of the new ideas, processes and institutions that health-sector reform demands. Furthermore, linking networks or groups of policymakers to local networks or groups mobilized around community health and related issues creates a strong enabling environment by facilitating advocacy and the direct engagement of community members in policy formulation, implementation and monitoring. These relationships enable the development of policies and programmes that are accountable and relevant and that respond to the real needs of communities and service beneficiaries. By building the internal capability and influence of community groups, including the socially marginalized, these processes can give voice to those normally not heard in policy debates and the decision-making arena (e.g. Morrison 2010; Kay and Datta 2010).

Moving forward: a three-step social capital-building process

These examples indicate the way the distinct types of social capital can be brought together and used in a systematic process to strengthen individual public health efforts and enable networks to achieve a range of goals. While each individual form of social capital has been shown to improve the health of individuals and communities, we propose a systematic, three-step process of bonding, into bridging, into linking that allows the benefits accrued in one community to extend outward through policy and other forms of social change.

Efforts to build and engage communities of people living with HIV in policy dialogue and change illustrate the value inherent in this process (HPI/USAID 2006). The Health Policy Initiative’s work to combat HIV-related stigma, for example, involved creating the conditions for meaningful involvement of person living with HIV (PLHIV) and most-at-risk populations in health policy and health-service delivery (Betron and Gonzalez-Figueroa 2009). It showed that greater investment in PLHIV networks (e.g. skills, programmes institutional capacity, resources—or bonding social capital), enabled more effective contributions of PLHIV to policy dialogue (through bridging with health providers and policy-makers), ultimately empowering PLHIV to influence the social and policy environments that affect their lives and health (linking with powerful bodies such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria).

Other efforts within HPI (now the Health Policy Project, HPP) strengthened the social capital of PLHIV through group networking (e.g. building skills for advocacy and stigma reduction), facilitating involvement of PLHIV as partners in project activities (action networking) and supporting the process of policy networking by linking these groups to national and regional policy-making bodies (e.g. Xia and Stephens 2011). In countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) where HIV prevalence is low but stigma is pervasive, the project linked those affected by HIV to key health service providers to create action networks, which in turn expanded to institutional relationships with national and regional Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), national AIDS control programmes, and research centres to inform policy and programmes, (Kay and Datta 2010; Hull et al. 2010).

Initially bringing people living with HIV together in training workshops (fostering bonding social capital), the Investing in PLHIV Leadership in MENA initiative (implemented 2005–10) strengthened skills and understanding of HIV basics among PLHIV, built capacity of HIV-positive women and men, focused attention on reducing HIV stigma and discrimination in health-care settings, and strengthened advocacy for access to treatment and stronger resource mobilization by local groups led by and for people living with HIV. The workshops provided a safe place for PLHIV to exchange ideas, express their concerns, form networks for mutual support and strengthen leadership skills. Subsequently small grants were awarded to groups of living with HIV in several countries to design, implement and manage local HIV activities. As the project gained momentum, regional networks were created (bridging social capital), bridges built to National AIDS Control Programmes, and links fostered to donors and international NGOs for fund and further support the burgeoning networks and to bring them into critical decision-making processes concerning programmes and services for PLHIV in the region (linking social capital). Kay and Datta (2010, p. iv) note that ‘The initiative, with its partners, fostered a shift in the region—from people living with HIV serving as beneficiaries to being increasingly and more meaningfully involved in the HIV response.’

The MENA Initiative’s process can be understood in terms of social capital by breaking it down into three discrete steps:

Bonding social capital was achieved through focused trainings and workshops led by and for PLHIV in the region, which were for some individuals the first time they had met and talked with others in their situation;

Bridging social capital was built when these individual bonded groups came together in a regional network led by and for PLHIV, known as MENA+, and strengthening in-country partnerships among PLHIV, national AIDS programs (NAPs) and NGOs.

Linking social capital exemplified initially by increased country ownership of NAPS around the region who pledged support and funding for participant costs and country-level activities. Further linking came through successful efforts to engage key donors and international NGOs. Successes here included a commitment from the Ford Foundation and the International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW) to support the formation of a regional network for HIV-positive women in MENA, and additional support acquired from partners including UNDP’s HIV/AIDS Regional Programmes in the Arab States, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), ICW, Ford Foundation, NAPs and local NGOs. In addition, this process increased participation of people living with HIV from the MENA region in national, regional and global HIV forums and in key decision-making positions including Global Fund Country Coordinating Mechanisms.

The projects described above did make a conscious effort to build social capital resources among groups of PLHIV, generating bonding social capital. They did not, however, follow a proscribed or systematic process of building on bonding, through bridging to linking the PLHIV networks with policy networks and groups. Rather it became clear through the process of implementation that in order for the participants to reach their goals they would have to engage in strategic network building, first with those closest to them (often health providers in their own communities), then upward to those with the ability to make and change policy. The understanding of the three-step process proposed, therefore, emerged out of post hoc reflection on this large body of experience. Deeper research into the growing universe of literature on social capital suggests that there is a sound theoretical explanation for why and how the process ‘worked’. Further engagement with this literature suggests that the process undertaken in the context of the stigma work could be applied to HSS and health policy efforts more broadly, discussed below.

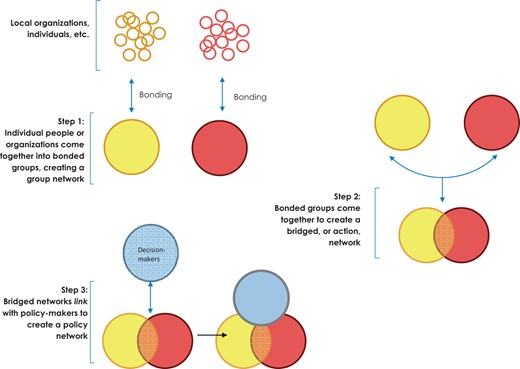

This three-step process—or model—for social capital building is depicted in Figure 1: Individuals coming together into bonded networks is Step One. Bonding is an important first step to build cohesion, increase inclusion and reinforce communications systems within a given group to increase equity. These networks exist as discrete entities, providing social support and building common vision and stores of influence among members until they bridge with other, like groups with shared goals, to create action networks in Step Two. Step Three involves horizontal linkages, usually ‘upward’, as these action networks seek strategic alliances with powerful groups of policy-makers, donors or others with the resources and/or influence to move the shared vision into meaningful change.

This is an additive process. Through bonding—or group networking—a community articulates a common need and creates bonds of trust and norms of reciprocity; through bridging (action networking), multi-community networks take purposeful action and in the process strengthen inter-institutional systems (providing, for example, referral systems in health-care settings for social and community services). As social capital initiatives expand beyond bonding and bridging to link these groups to sources of power and influence (policy networking), there can be a direct impact on health governance, policy and, in turn, on the quality of programming and the strength of health systems.

Building social capital for stronger health systems

In the context of HSS, this additive three-step process can support HSS objectives through strengthening the building blocks of a health system (WHO 2007, see Box 1). For example, relating to the use of information, medical products, vaccines and technologies, when previously disparate groups of practitioners and policy-makers come together in bridged action networks, the ‘weak ties’ formed greatly facilitate the diffusion and ultimate uptake of new ideas, information and technology among and between provider networks. These ties can likewise facilitate the flow of information, new norms, identities and practices from one group to another. New information about emerging best practices, improved access to new technologies and normative pressure to improve the quality of services can enhance the performance of individual providers and the overall quality of health-care delivery.

1. Service delivery

2. Health workforce

3. Information

4. Medical products, vaccines, and technologies

5. Financing

6. Leadership and governance

By bringing together otherwise siloed practitioner communities in trust-based networks with a common goal (group networking into action networking), social capital can support the processes of service integration. The integration of HIV and reproductive health services offers a salient example. In this case, the rationale for integration has long been considered incontrovertible. Action has been hampered, however, by vertical programming and funding structures that foster competition between programmes rather than promoting understanding of common cause, trust and reciprocal relationships, a situation aggravated by a lack of advocacy for better co-ordination from the grassroots (Berer 2004; Ringheim et al. 2009). The political will and an enabling environment for integration could be generated by building bonding and bridging social capital within the health sector and within communities galvanized around the common goal of improved outcomes for women and families. Linking community advocacy groups to health sector networks would create strong incentives for sustained action and improved programmes, quality. Expanding these networks across sectoral lines can catalyze new energy, purpose, and a common vision for an intersectoral approach to health.

In Better Together: Linking Family Planning and Community Health for Health Equity and Impact, Ringheim (2012) makes a number of recommendations that can apply a social capital approach: engaging communities in improving service delivery and generating demand and support for sustainable community-based services; overcoming resistance and building trust by involving men, youth, parents and religious leaders in awareness raising; linking communities with district health staff to share data and increase visibility and developing community capacity to carry out monitoring and evaluation activities.

Building social capital can also support the leadership and governance building blocks. The foundation of health system stewardship is a government’s commitment to steering the entire health system toward equity and in protection of the public interest. It involves developing appropriate health-sector policies and frameworks, as well as ensuring accountability, the appropriate use of data, and coalition building within the health system (including the private sector), across government sectors (for ‘Health in All Policies’ or ‘joined-up’ government), and between the health system and the communities it serves. Thus by creating strong group networks focused around health service quality at the community level (group networking), connecting these groups to relevant providers and activists with similar goals (action and policy networking), considerable pressure can be brought to bear from the ground up to create change.

The Rwanda Reproductive Health project illustrates the synergies between policy change at the state level, citizen participation and social accountability (Chambers 2012). In post-genocide Rwanda, earnest efforts were made to ‘build a collective vision of a common future’, harnessing key governmental institutions ‘in innovative ways to provide practical inducements and inputs into participatory planning processes. These arrangements have helped to create a local environment that is generally conducive to change’ (Chambers 2012, p. 2, emphasis added). Upward accountability mechanisms are fostered through the creation of clear lines of authority among the different agencies responsible for implementing government policy on maternal health. These mechanisms are accompanied by ‘consistent incentives—moral and material rewards and sanctions—that ensure actors are motivated and work toward the same goals’ (Chambers 2012: 3). Local engagement and citizen participation are encouraged through integrated public health education efforts and through the creation of savings clubs and social insurance schemes. This example illustrates that the state can, and perhaps must, play a key role in facilitating the healthy behaviour choices of citizens. Building social capital within the health sector and between health and other relevant sectors plays a critical role in establishing this practice on the ground.

The experience of the WRA is an example of bonding, bridging and linking social capital at work to transform policy and strengthen health systems. Since its launch in 1999, WRA-India has found that a critical issue for maternal health in India is the failure to implement existing policies and programmes (USAID/Health Policy Initiative 2010; Gogoi et al. 2012). To pressure the government to act on its commitments, WRA-India developed what it calls a ‘social watch’ methodology (USAID/Health Policy Initiative 2010). This social accountability approach creates momentum for change at the community level starting by building bonding social capital among members, then raising awareness more broadly through public hearings, and proactively creating bridges to influential community voices, such as the media to develop national campaigns. The group created further bridges with groups of sympathetic providers, and through these efforts put pressure on politicians and the health system (linking social capital) to create change. In 2006, the programme adapted George’s (2003) social accountability framework, which posits that successful social accountability requires information, dialogue and negotiation through which engaged communities can ‘confront power relations, improve the representation of neglected issues and people, and transform the way in which participants view themselves’ (Gogoi et al. 2012). The WRA-India project sought to meet these ambitious objectives by generating demand through public hearings, leveraging intermediaries, and sensitizing leaders and health providers to change their mindset.

Although the mechanisms through which WRA-India operates do not involve the creation of formal networks or groups per se, the public hearings generate enough social capital that women are able to speak out about their negative experiences with maternal health services. Politicians are invited to these hearings and feel the full force of the citizenry’s disapproval of their performance, in some cases changing policy on the spot (Gogoi et al. 2012). The public hearings also put pressure on service providers who thereby become more accountable to improve the quality of care. They build on the sense of common cause and community that are generated when people come together and connect around an issue of mutual concern, and directly carry their voices to sources of power to create policy change. In this way, the hearings create normative pressure on policy-makers and providers to change their practices—complete with clear sanctions for non-compliance to the community’s demands.

The limits of social capital

In the real world, bonded groups may face a multitude of barriers in their efforts to build effective action and/or policy networks. As Bourdieu (1986) suggests, those with power do not always see it as in their own best interest to include the less powerful in their circles. Bourdieu notes that social capital is often rooted in economic capital and therefore tends to accrue to those with greater access to resources—both economic and symbolic or cultural. Wakefield and Poland (2005) review a broad range of critiques of the social capital concept as applied to health promotion and development, emphasizing that application of the concept must be undertaken thoughtfully, with attention to potential pre-existing class, race and gender dynamics (see also Foley and Edwards 1999; Morris and Braine 2001).

It is clear, therefore, that focusing on social capital in the absence of parallel efforts to build political will for change will constrain outcomes. The political context in which community social capital is fostered is crucial: if the will for creating effective linkages with communities is absent, the promise of community social capital for sustainable improvements in health is jeopardized (Baum 2007; Dickinson and Buse 2008; Parkhurst 2012). In South Africa, for example, one programme effectively built bonding social capital among a group of women caregivers in a community. However, it ultimately failed to sustain the momentum of the group because there was a lack of political will among politicians and local men to link the group with sources of power and influence (Gibbs and Campbell 2010). As Baum points out (2007, p. 94), ‘Linking social capital suggests a policy approach that is trustful of communities, encourages them to do the right thing … and provides them with the infrastructure to create a health-promoting environment.’ In contexts that are not oriented around equity or trustful of communities, social capital approaches may be most effective when linked with community mobilization and structural interventions that focus on challenging existing power structures and addressing entrenched structural drivers of health inequity. A framework such as this should assist with measuring social capital processes and effects on social mobilization, social equity and policy change.

Additional work is needed to explore how social capital can be brought together with the social accountability framework (George 2003; Gogoi et al. 2012) or other normative frameworks (e.g. Wilson 2009; Parkhurst 2012) to create a culture of concern and genuine ‘service sincerity’1 among those charged with health policy and programming at all levels of the health system and across national contexts.

A key challenge in applying the proposed model—or process—lies in the lack of clear mechanisms to facilitate or systematize linking social capital (policy networking). While bonding and bridging social capital can occur or be catalyzed with few systematic inputs, linking social capital requires that systems and mechanisms—as well as the will—for engagement are in place and functioning. Governments, in partnership with NGOs, Community Based Organizations (CBOs) and other community partners must proactively find ways, ideally using existing channels, to (a) make linking happen across a number of different institutional, community, and policy communities; (b) put in place incentives and sanctions related to their appropriate use and (c) monitor progress and impact. In the absence of this proactive approach, social capital processes risk stopping at the level of bridging, thus seriously compromising the ability of these processes to foster stronger governance and improve programming quality within the health system. The institutionalization of a three-step social capital-building process would allow for both targeted, health sector specific ‘wins’, while facilitating wins across a range of development sectors with impacts on health.

Conclusion

Although the role of social capital for health and HSS has been the subject of debate (e.g. Lynch et al. 2000; Pearce and Davy-Smith 2003), and concerns about social capital and equity prevail (Wakefield and Poland 2005), developments in social capital scholarship (Szreter and Woolcock 2003; Gibbs and Campbell 2010; Campbell et al. 2009; Kawachi et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2006a, b) and a growing number of operational examples across global settings suggest that the social capital that accrues to marginalized as well as mainstream groups through strengthened networking can positively influence health policy, health systems and health system accountability. Social capital supports health policy and HSS by improving collaboration and communication within health systems, across government sectors and, crucially, between health systems and the individuals and communities they seek to benefit (WHO 2007; Global Fund for AIDS, TB and Malaria 2010).

The application of social capital ideas to public health problems is not new. For years, health and other social policies and programmes, have built social capital, although they did so using the language of social participation, community engagement, networking and alliance building. This article contributes to these trends by proposing a simple three-step social capital-building process to create a more systemic response to community health needs. It calls for the creation of issue-focused, cohesion-building group networks within communities and communities of practice, the development of action networks connecting these groups and the further linking of these bridged groups into policy networks. This process fosters intersectoral dialogue and co-operation and improved grassroots participation in health care.

Rather than being a way to abandon communities, as some early critics feared (e.g. Pearce and Davy-Smith 2003), social capital can be actively generated through HSS and policy processes to ensure that policy-makers are held accountable for meeting real needs. Social capital can be a vital resource within and among policy-making and practitioner communities in the process of HSS, as it facilitates communication and the flow and application of new norms, values and ideas. Building social capital within the health system and within and between networks of providers and other sector-focused networks creates incentives for compliance, and sanctions for non-compliance, through moral and professional pressure to conform to new norms. A response to health needs that incorporates social capital, therefore, must be seen as a sustainable part of an effective response—not as a ‘nice but optional’ add-on to policy-making as usual.

The process of building social capital can support health policy and HSS. When approached from a position of service sincerity, it offers great potential for the creation of trust, norms of reciprocity, rights and sanctions across the health system and reaching into the community. A systematic approach to building social capital can foster good governance and health system accountability, and improve social equity while ensuring meaningful and ongoing participation of communities to create a stronger, more effective health-care system for all.

Acknowledgements

This article was written under the Health Policy Project (HPP), a five-year co-operative agreement funded by the US Agency for International Development under Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-10-00067. HPP is implemented by Futures Group, in collaboration with CEDPA (a part of Plan International USA), Futures Institute, Partners in Population and Development, Africa Regional Office (PPD ARO), Population Reference Bureau (PRB), RTI International and the WRA.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Endnote

1 This phrase was coined by a participant in the WRA-India case study on social accountability. We borrow it here with permission.